Table of Contents

You’ve heard of DLS and you’ve also heard of DRS, but what about VJD? I must admit, this term was new to me and I was eager to learn more.

What is the VJD Method in Cricket?

The VJD Method is a means of calculating revised targets in a rain-affected cricket match. It is similar in that sense to the existing Duckworth Lewis Stern method, but it seeks to address perceived weaknesses in that system.

The VJD Method was devised by the Indian Civil Engineer V. Jayadevan and it has been used in a limited number of domestic competitions.

VJD Method of Calculation

The VJD Method takes into account the likelihood that a batting side will accelerate towards the end of a match that has been affected by the weather. After an interruption, there is a tendency to speed things up.

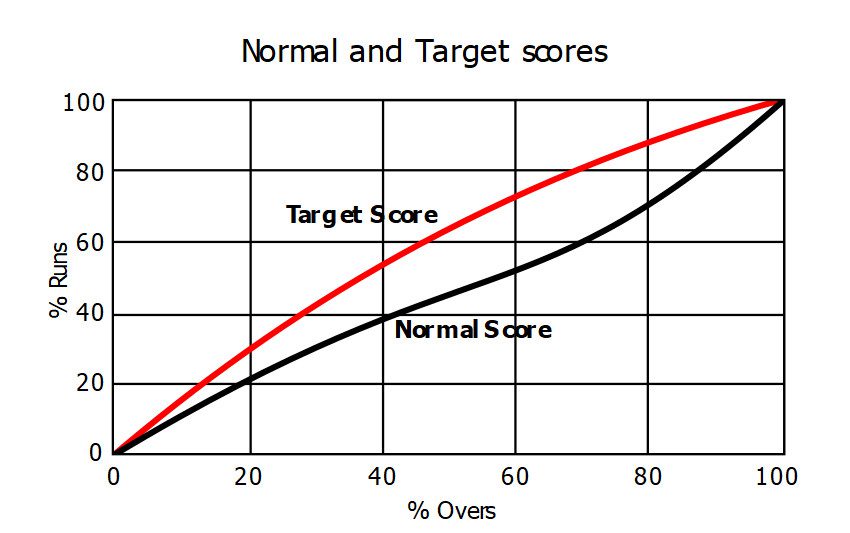

The system works on two curves on a graph. The first curve shows a normal run rate in a game that lasts the full distance. The second curve allows for that acceleration in a match where the weather has forced the players off the field.

The first curve is the ‘normal’ curve and it takes into account wickets lost and overs bowled. The second curve is referred to as the ‘target’ curve and it solely focuses on run rate.

Things begin to get a little more complex from this point. Intricate calculations are used to identify what the target should be for the side batting second.

VJD uses seven scoring phases as the basis of its calculations. It all starts with overs 0-15 before progressing to 6-15 and finishing with 46-50.

The system uses mathematical models to assess scoring phases in those early overs. It then applies a prediction, based on likely acceleration, as to what the final score might be. By crunching all of those numbers, VJD then calculates the likely target for the team batting second.

In the very few games that have employed VJD, the batting side then has a target that they need to reach in order to win the game.

History of VJD Method

There isn’t a clear date as to when V Jayadevan invented his method. We can only assume that he had been working on it for some time before it began to emerge in the first decade of the new century.

The VJD method was originally lined up to be used in the 2011 edition of the Indian Premier League. The plans were in place but they didn’t go ahead.

We have, however, already seen VJD in other competitions. The Indian Cricket League and the Tamil Nadu Premier League have both used the system to decide rain-affected games. Overall, there has been little take up to date, but that may change in the future.

DLS Method vs VJD Method

The big difference between DLS and VJD is the issue with the acceleration in scoring. In Duckworth Lewis, the system assumes that the scoring rate will remain the same, before and after any interruption.

With the V. Jayadevan Method, it works on the theory that a run rate will increase following a break in play that leads to a shortened match.

Duckworth Lewis also takes into account the number of wickets that are left. If you watch a game where DLS is in play, you’ll see that the target score will increase at the fall of a wicket.

VJD also disregards the number of overs left. Its calculations are purely based on what it sees as a natural increase in run scoring as the innings progresses.

Conclusion

I admit that the VJD method is new to me, despite the fact that it’s already been used in domestic cricket. I personally think there is room for a new method and the VJD system certainly has some positive points.

It seems right to assume that run rates will increase in a shortened match. If we look at T20 cricket, run rates of 10 and above are common. In 50-Over matches, no side has yet maintained a run rate of 10 across their entire innings.

The one area where I’m not so convinced relates to wickets. VJD suggests that the run rate will not be affected by the loss of wickets, but is that right? After losing one or two quick wickets, a team may naturally be more cautious – even if it’s just for the next few deliveries.

That’s why there is some value in the VJD Method, but the ICC seem happy to use DLS for now. Could that situation change? It’s all down to whether individual leagues and knockout competitions decide that they want to use it.

Clearly, if the IPL had introduced the method in 2011 as planned, we’d all know a lot more about VJD. I really think there are some merits and it will be interesting to see if the VJD Method is used more extensively as an alternative to DLS in the future.